Last week I looked at Nature's data policy and was corrected by Eli Rabett on the existence of a formal policy. ER pointed to Nature's advice to authors at the time of Phil Jones' 1990 paper on urban heat islands:

Nature requests authors to deposit sequence and x-ray crystallography data in the databases that exist for this purpose.

As he notes, this paltry sentence doesn't support the idea that there was a formal policy in place requiring authors to make data available. However, Shub Niggurath has been doing some research, and I think his findings put this lone sentence in some perspective, which is quite interesting.

For a start, the sentence in question comes from a guide for authors, a document mainly concerned with the intricacies of style and formatting. To get a broader idea of Nature's approach to data availability, we have to look elsewhere. Useful information comes from an essay by the editor of the time, John Maddox.

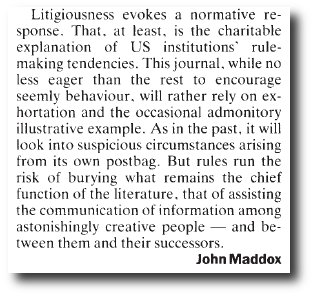

Data ownership and access were causing concern in scientific circles, especially in protein biology and genomic reseach. Discussing the suggestion that data availability should be a precondition of publication, the great man opined:

:

This confirms the idea that there was no formal policy, but seems to suggest strongly that Nature felt that authors were under an obligation to make materials available.

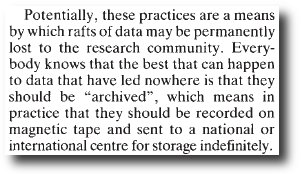

Shortly before Jones published his paper, Maddox introduced a new facility for authors - the ability to deposit supplementary information - the extraneous data that supported a paper's findings. As Maddox noted, with larger and larger amounts of data being processed, there was a real risk that important and useful data would be lost...

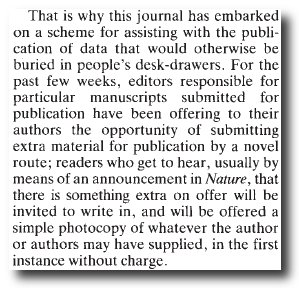

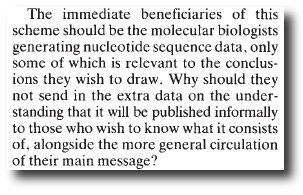

With that in mind he announced an innovation to address the problem - the journal would host the material and send out copies to scientists who requested it. Although this was directed primarily at molecular biologists, there was no suggestion it was exclusive.

With that in mind he announced an innovation to address the problem - the journal would host the material and send out copies to scientists who requested it. Although this was directed primarily at molecular biologists, there was no suggestion it was exclusive.

There is no suggestion that this was compulsory - in fact quite the opposite; it seems to have been assumed that scientists would want to make use of the facility.

There is no suggestion that this was compulsory - in fact quite the opposite; it seems to have been assumed that scientists would want to make use of the facility.

This would appear to explain the "policy", if I can dignify the words at the top of the post with that term, in a certain amount of perspective.

This would appear to explain the "policy", if I can dignify the words at the top of the post with that term, in a certain amount of perspective.

It all seems very old-fashioned and gentlemanly, with an assumption that everybody in science wants to behave well. One does wonder what Maddox would have thought authors failing to produce data central to a paper's claims.

So Jones was under no obligation to release his data? Not quite: examination of Doug Keenan's correspondence with Nature suggests a different conclusion. Having failed to get the Chinese station data from Jones and Wang, Keenan approached the journal about the possibility of making a materials complaint. While Keenan didn't pursue the matter with the journal, there is no hint in the correspondence that that Nature felt Jones had an option not to deliver up the information Keenan wanted. Indeed, the journal was quite clear that they would admit a materials complaint, provided the request was "reasonable". In the event, they simply said that if Jones no longer had what Keenan wanted there was little they could do to help, but it is clear that they felt that if Jones had them, he should release them.

This series of postings began with by considering confidentiality agreements and their implications for journals. In the case of Jones et al 1990, there were no such agreements in place, and it is clear that the journal felt that Jones was obliged to release his data, formal policy or not. How they would view a refusal on the grounds that confidential information had been used is an interesting question, which takes us quickly into the realms of unreplicable science.

But that's a question for another time.

Shub Niggurath has a related post here.